We’re counting down to the Archtober Festival!

Start exploring October events here.

Shop

Take home a piece of the festival

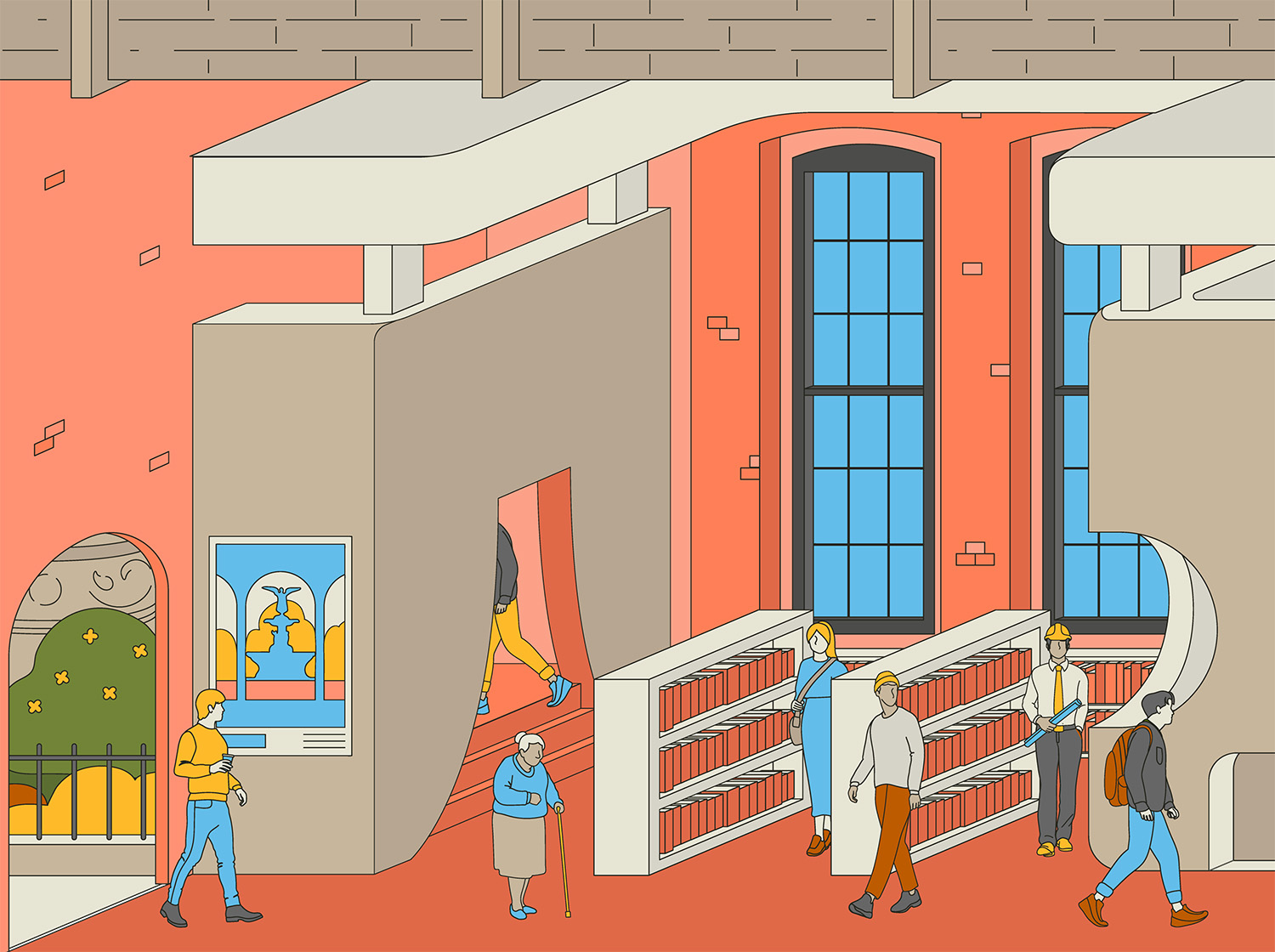

This series highlights a festival illustration (created by Greater Studio) and features a short Q&A about the organization or initiative featured.

In conjunction with the Archtober 2025 festival theme, Shared Spaces, we're celebrating the city’s public life with a closer look at the series of illustrations depicting various public spaces around NYC, from Little Island to Luna Park to the Roosevelt Island tramway—to Adams Street Library! This series highlights a festival illustration (created by Greater Studio) and features a short Q&A about the organization or initiative featured.

Designed by WORKac, Adams Street Library is Brooklyn Public Library’s first new branch to open in more than 20 years. Adams Street was awarded an Honor in the Interiors category of the 2023 AIANY Design Awards. The project is featured in our Archtober Coloring Sheets, available to download and print for free. Hear more about the project from the WORKac design team in our Q&A below!

Q: Adams Street is the first new Brooklyn Public Library branch in over 20 years. How did that legacy influence your approach to designing this space?

Designing a new library today is really about rethinking what a library is—not just a place for books, but one of the last truly public spaces where people from all walks of life can come together. Libraries have taken on a renewed importance as civic hubs: places of connection, learning, and refuge in cities that are becoming increasingly privatized.

Being the first new Brooklyn Public Library branch in more than two decades carried a sense of responsibility. We wanted Adams Street to embody that larger civic role—to be open, visible, and welcoming to everyone, from long-term residents to newcomers. In many ways, the project became a way of expressing our belief that architecture can help sustain and even strengthen community life. It’s about designing for access and generosity, creating a shared space that reflects the evolving ways we gather, learn, and imagine our collective future.

Q: What role did community feedback play in shaping the design, especially when thinking about shared spaces and focusing on children’s programming?

The community engagement process was really the foundation of the project. We met with residents from DUMBO, Vinegar Hill, and the Farragut Houses, listening carefully to what the neighborhood wanted and needed from a new library. Again and again, people spoke about the lack of spaces and programming for children. That input was so consistent and so strong that it truly shaped the entire concept.

The design process took that feedback to heart and placed children at the center of the library—both literally and symbolically. We wanted young people to feel that this space belonged to them and that families could find a place to gather, learn, and grow together. It was equally important to provide teens with their own area, reflecting the different ways they connect and engage. In the end, the library became a direct reflection of the community’s voice and aspirations.

Q: The library includes large multipurpose rooms and flexible furniture—how important was adaptability in your design? How did you approach designing a space that balances individual use with communal experiences?

Adaptability was a key idea from the beginning. Libraries today are asked to do so much more than they used to; they serve as classrooms, event spaces, study halls, and gathering places. We wanted Adams Street to shift easily between all of those roles.

Flexibility, for us, isn’t just a design feature but a reflection of how public life works. Communities evolve, and the spaces that serve them should be able to evolve too. At Adams Street, that meant creating areas that can host a workshop in the morning, story time in the afternoon, and quiet reading in the evening. It’s about designing a place that supports both focus and exchange, where people can be alone together.

Ultimately, we wanted the building to feel alive, responding to the rhythms of the community and support many kinds of connection, whether it’s a child discovering their first book or neighbors coming together for a community meeting.

Q: Can you share how the context of the area’s historic district and the adaptive reuse of the facility inspired the vision for the design?

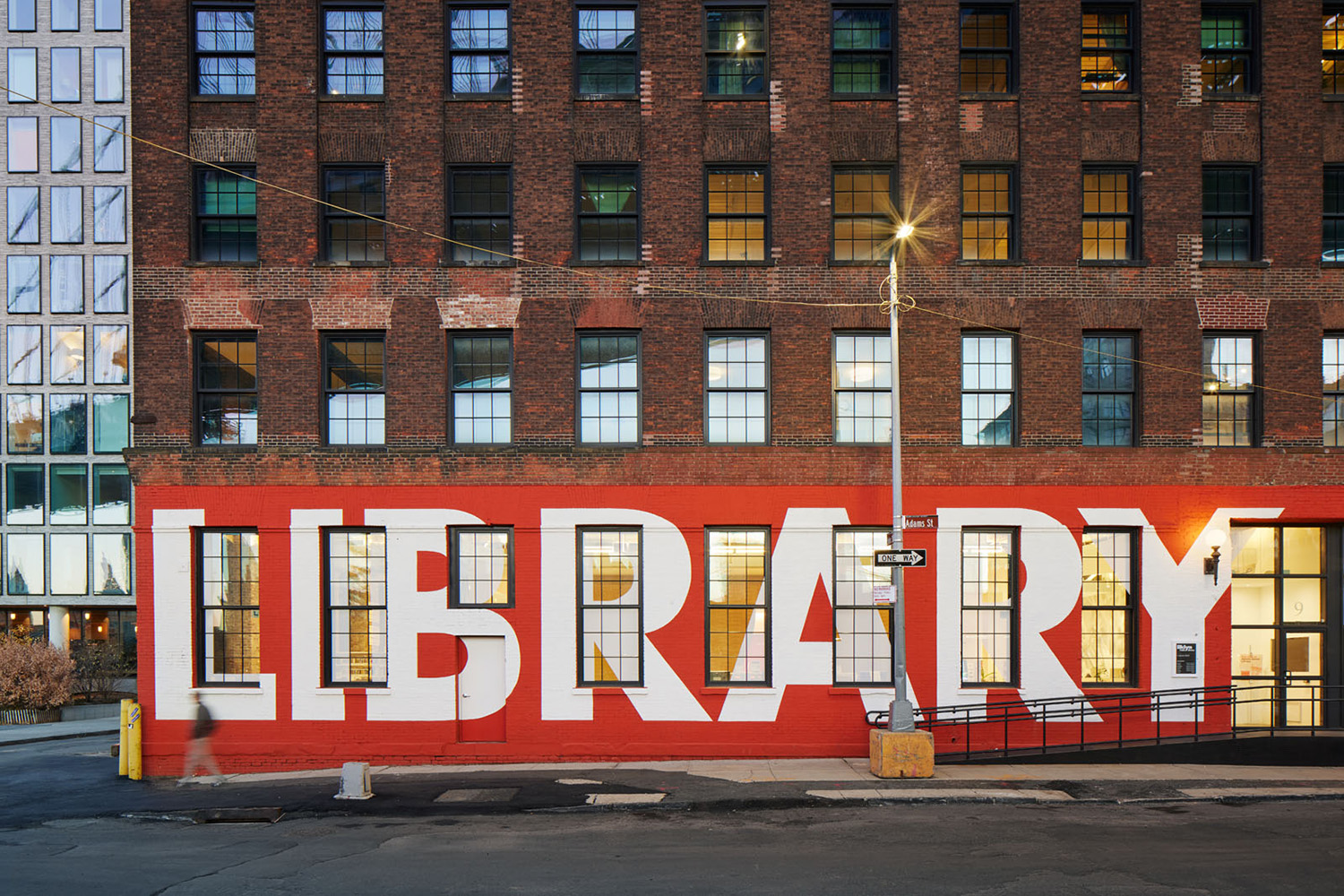

Working within an old industrial building under the Manhattan Bridge was both a challenge and a gift. We were very conscious of not erasing the building’s history; it had been many things before becoming a library, from a torpedo factory to a recycling plant, and we wanted that layering to remain visible.

The contrast between the building’s raw structure and the new interventions became part of the story. It reflects the neighborhood itself and how DUMBO has evolved while still carrying traces of its past. Keeping those traces felt important, especially in a city where change often means replacement. Even the hand-painted sign on the façade draws from that history, referencing the old signs still visible on DUMBO’s brick warehouses. It was our way of honoring the neighborhood’s visual language while giving it a new civic presence. We wanted to show that preservation and transformation can coexist, and that new public life can emerge from historic buildings.

Q: What does “public space” mean to you in the context of architecture, and how did you manifest that idea physically in this library? What do you think this library says about the evolving role of public spaces in cities today?

Public space has always been at the heart of our work—it’s where architecture meets the everyday. For us, designing public buildings is about generosity, about creating places where people feel seen and connected.

The Adams Street Library tries to make that idea tangible. It’s open and visible to the street, it connects to the park and the river, and it announces itself proudly as a public building with a big ‘LIBRARY’ sign that you can see from across the East River. In a time when so much of urban life is mediated or commercialized, the library stands for something different. It’s free, it’s shared, it’s collective.